Thinking About Your Business Structure

The legal structure of your business makes a difference to taxation outcomes, protection of assets from attack by creditors, the ability to raise capital and the financial and estate planning outcomes of your ownership and eventual exit from the business.

The decision on how to structure your business is a complex and important one that involves a number of considerations, not all of which have equal importance

to all people. And their importance to you and your family will change over time, as personal and family circumstances change.

Also, we need to be mindful that the legislation with in which you are making this decision will change over time. A good decision under the laws as they presently stand can become a bad decision if the laws change.

This Special Report discusses the main issues on business structuring and incorporation. The discussion is necessarily fairly general, as each set of

circumstances are different and there may be other considerations specific to you. In any event, you should not take action until you and DBA Accountants have thought through the issues raised here and fully discussed the issues and how they apply to you and your business.

DBA Accountants are specialists in family business, professionals and investors, and we support our clients in every area of their financial affairs. In providing our support, we will do anything in our power that is legal, moral and ethical.

What is “Incorporation”?

Incorporation is the process by which an organisation adopts legal structures that make it a legal entity in its own right, a “corporation”. It becomes legally separate from its owners. A company (eg. DBA Accountants Pty Ltd) is an incorporated business and a sporting club or non-business group with “Inc” (sho

rt for “Incorporated”) after its name is an incorporated association, eg. XYZ Baseball Club (Inc).

In Australia, companies are incorporated in accordance with the Corporations Act 2001. In Western Australia, associations and clubs are incorporated under the Associations Incorporation Act. Other states and territories have similar legislation.

Unincorporated Enterprises

A trust is not an incorporated entity (more on this later).

Individuals trading in their own right are called “sole traders”. The individual is not legally separate from the business. They are the business and all of their assets are available to the creditors of their business.

Partnerships are when two or more entities (individuals or corporations) join together for a business purpose. Joint ownership of an investment, such as a rental property, is not a business for the purposes of the Partnership Act.

A common misunderstanding is when individuals register a business name, such as “XYZ and Company” and think that, because the word “company” appears in their business’ name, they have a company within the meaning of the Corporations Act. They do not. What they have is a legal right to use the words “XYZ and Company” as a name for their business.

The main advantage of sole tradership or partnership is that the only costs of setting them up are:

- Applying for and acquiring an Australian Business Number (“ABN”) and for a partnership, a Tax File Number (“TFN”). A sole trader uses their own TFN.

- Applying for a registered business name and paying the ASIC fee. Registered names are known variously as a “trading name” or “business name” but the legislation now refers to “business name”. It is an offence to trade under a name that is not your own name or a registered name owned by you.

The main disadvantage is that partners and sole traders have unlimited liability for the debts of their businesses. This means the whole of their personal estate is available to creditors of the business, should the business fail. Partners are jointly and severally liable for the debts of their business – meaning, the creditors can pursue whichever partner they think has assets to be taken. Or, as happens, the partner they can actually catch!

Most businesses involve risk, so generally speaking, only very small businesses are suited to unincorporated structures.

In a limited partnership, there is usually General Partner and at one or more Limited Partners. The partnership is structured such that the General Partner has unlimited liability and so is probably a pty ltd company, and the Limited Partners have limited liability.

A taxation advantage of sole traders and partnerships is that any trading losses (not capital losses) incurred in the business can be used as an offset against other incomes in the personal tax returns of the sole trader or the partners. That is, providing the Non-Commercial Loss provisions are met.

Sole traders and partners pay income tax on their profit or share of profit. They do not have an employer withholding tax from their wages. Some sole traders and partners find it difficult to budget for their payments of income tax and quarterly instalments of tax. At DBA Accountants we help our clients manage this situation by looking ahead and forecasting the likely tax assessment and then if necessary, creating and implementing strategies for payment.

Incorporated Associations

Typically, these are sporting, social and cultural organisations, operating for the promotion of their sport, or for the mutual benefit of members. Incorporating under their state legislation provides limited liability to the members of the governing committee(s) of an association.

Many associations also operate a business, such as a dining room or bar, open to members and guests. They lodge a company tax return in respect of these business activities and pay tax at company rates on their business profit.

Reasons for Incorporation

There are many circumstances in which you might consider incorporating your business. The more important reasons we find ourselves dealing with are:

- To provide you, the business owner, with limited liability so you are not personally liable for the debts of the business

- To protect other assets by isolating the risks of this business – we speak of “quarantining” the assets

- To create a clear succession path for you to eventually exit the business – we speak of an “exit strategy”

- To hold assets in a company name for the sake of separately identifying them

- To give your business activity an appearance of substance

- To meet a condition for obtaining work

- To manage the assessment and then payment of taxation

Typically, the incorporation of a business would result in a corporate structure comprising one or more companies and trusts.

What is a Trust?

Legally, a trust is a set of contractual obligations set out in a document called a trust deed. A trust is not a legal entity in its own right because it is not a person and it is not an incorporated entity such as a company. Because of this, a trust cannot enter into contracts in its own right – the trustee of the trust enters into contracts on its behalf.

A trust with a company as trustee enters into a contract through its trustee in this way:

“XYZ Pty Ltd (ACN 00 123 456) as trustee for ABC Trust (ABN 123 456 789)”.

A trust with individuals as trustees would sign like this: “John Charles Smith and Mary Florence Smith as trustees for ABC Trust (ABN 123 456 789)”.

Often the expression “as trustee for” is abbreviated to “ATF”.

The trustee is liable for the debts of a trust. Therefore, in a situation where the trust is taking risks, the trustee would normally be a company, for the reasons given above. If risk is not a concern, for instance, if the trust merely invests and receives dividends and interest, it may be appropriate for one or more individuals to act as trustee.

A trust is a “flow-through” structure. The whole of its net income flows through to the trust beneficiaries (or unit holders, if it is a unit trust) each year. The trust pays no tax if it distributes all of its income.

Beneficiaries and unit holders of trusts receive their profits with no tax withheld. The trustee of each trust then has the opportunity of distributing the trust income around their own family, to manage the taxation consequences, and without needing to refer to their fellow unit holders or beneficiaries.

There are various types of trusts:

A “bare” trust is where a trustee holds an asset in trust for another person. For instance, a parent holds a bank account in trust for a child. Or, a company holds a piece of real estate in trust for the members of a superannuation fund.

A “discretionary” trust is one where the trust deed allows the trustees discretion as to the distribution of trust income and capital. It would be usual for the trustees to exercise their discretion after considering, among other things, the taxation consequences of their action. These are often referred to as “family” trusts because of their common use in channelling income to family members.

A “unit” trust is one which issues “units” of capital to “unit holders” and distributes its income and capital in accordance with the number of units held by unit holders. The trustees have no discretion. It can raise more capital by issuing new units to investors. Unit holders are able to transfer their units to others.

A “hybrid” trust is a unit trust in which there is a class of units for which the trustees have discretionary powers.

A superannuation fund is a trust but a super fund cannot operate a business.

What is a Company?

A company is an incorporated entity. It is governed by a Board of Directors and the Board employs staff to whom the operation of the companies’ business is delegated. In most family business situations, the Board are family members and the main employees are often also the Board members.

There are different types of companies. The most common form of company used by the clients of DBA Accountants is a proprietary company limited by shares, called “proprietary limited”. They are usually known as “private” companies, because (typically) they are owned by one or two families and they are not required to make their financial information publicly available.

A proprietary limited (almost always abbreviated to “Pty Ltd”) company is a legal entity separate from its owners, the shareholders, in the same way that one person is a separate legal entity to each other person. It is able to own assets and incur liabilities in its own name. It can sue and be sued in its own right. It pays tax in it’s own right. The “Proprietary” part of the name indicates the entity is incorporated under Australian Corporations Law as a “proprietary” company limited by shares, with these limitations on it:

- * It can have any number of shareholders who are employees and up to 50 shareholders who are not employees

- Shares can only be transferred with the approval of directors

- It cannot approach the public at large for capital

The “Limited” part of the name indicates that the shareholders’ liability to the company is the amount they have agreed to pay for their shares. This means that if a shareholder has agreed to pay $5 for a share, they are liable to pay the company the agreed $5 and no more. The assets of a company are available to its creditors, but those creditors cannot claim against the assets of the shareholders, the company’s owners.

Limited liability is the main reason for operating a business through a company, particularly for a large business or a business with high trading risks.

What is “Limited liability”?

“Limited liability” means that the liability of shareholders is limited to the amount they have agreed to pay for their shares. The shareholders are not liable for the debts of the company unless they have given personal guarantees for those debts. This is particularly valuable in a situation where the business involves risks such as those related to trading in goods, actions for negligence or safety, product liability and contractual obligations.

To explain by way of an example:

A company might issue shares to its shareholders at $5.00 per share but only require the shareholders to pay $1.00 per share at the time of issue.

Those shareholders are liable to pay the company a further $4.00 per share, should the company ask them to do so.

Each shareholder’s liability to the company is limited to that $4.00 “uncalled” amount per share.

After the shareholder has paid the contract share price ($5 in this example) they have no further liability to the company in their shareholder capacity.

If the business risks are taken in a limited liability company or in a trust with a limited liability company as its trustee, the personal assets of the shareholders are protected to the extent allowed by law. In some situations, we create structures where one entity owns all the assets and these are hired to an operating entity that carries out the work and takes the risks but owns very few assets. The valuable assets are quarantined from the creditors of the operating entity, providing appropriate ownership registrations are in place.

The benefit of limited liability for the shareholders and directors of small companies is often lost if the company needs to borrow money. Almost without exception, a lender to a company will require personal guarantees from directors, so if the company cannot pay, the directors must. The assets of directors can become available to creditors as a consequence.

Also, directors have personal liability for PAYGW not paid to the ATO and compulsory superannuation for employees not paid to super funds.

Succession Planning

Eventually, you will wish to sell your business or you will wish to invite other investors to participate in the ownership of the business – family members, for instance, or outside investors.

When setting up your business structures, it is important to think ahead to how you intend exiting them. The structure you create today needs to make it easy to implement your exit strategy at some time in the future. For instance, if the business is owned by a company or a unit trust, the company or trust can issue new shares or units to investors, or existing investors can sell some or all of their shares or units to new investors.

A discretionary trust has no units or shares and so cannot sell a piece of itself.

Identification of Assets

As part of an asset protection strategy, it can be important to hold an asset, or group of assets, in a separate entity, such as a company or company as trustee of a trust. The separate entity would be distanced from other entities which might be involved in risky activities and never, ever enters into a guarantee for any other entity.

Ownership by a company, or a company acting as trustee of a trust clearly identifies assets as belonging to that company. Ownership by a person acting as trustee could confuse creditors into believing the asset was owned by that person in their own right. The creditors might then attack and the person would need to defend themselves and the asset – win or lose, this would be expensive in money and emotion.

The cost of incorporating and accounting for a company may be justified by the value of being able to sleep easy at night.

Appearances

Sometimes there is value in incorporating solely to give a business an appearance of substance. A business called “XYZ Pty Ltd” can seem more impressive than one called “John Smith trading as XYZ”. If this impresses customers and helps in winning business, we suggest you do it. In the same way, a business not registered for GST is necessarily, a very small one.

For some businesses, it may be worth registering just for the sake of appearances.

Obtaining Contract Work

It is reasonably common for large corporations engaging contractors to insist that the contractor be a proprietary limited company. They do this to avoid any suggestion the contractor is an employee, with attendant obligations to the employer. A pty ltd is not a person and cannot be an employee.

In this situation, if you want the work, you pay the price and incorporate.

Taxation of Income

Our discussion here is solely related to Australian resident taxpayers. Non-resident taxpayers are taxed according to slightly different rules.

Sole traders and partners pay income tax on their profit or share of profit. They do not have the power to distribute profit in the way a trust does. The whole of the year’s taxable income is taxed in their hands.

A trust does not pay tax unless the trustees fail to distribute all the trust’s net income. A trust only withholds tax from a distribution if the beneficiary has failed to provide a TFN or is a foreign resident subject to non-residents’ withholding tax. The income distributed by a trust is taxed in the hands of the beneficiaries.

Tax planning and estate planning opportunities arise if trust income can be directed to beneficiaries with low incomes, or with losses. Trust income would probably be directed away from beneficiaries facing bankruptcy or divorce.

When individual beneficiaries are faced with receiving distributions that push their personal incomes into higher tax brackets, the trustees will consider incorporating a company to receive distributions. This company might use its distributions to make loans to family members or family businesses. Or, it might acquire assets to be hired to the operating entity. The ATO refers to such companies as “corporate beneficiaries” because they are corporations whose role is to be a trust beneficiary. We at DBA Accountants call them “bucket companies”, being the bucket into which all surplus trust income goes.

Unit trusts distribute their income according to the number of units held. It is common for units in unit trusts to be owned by discretionary trusts, to take advantage of the trustees’ discretionary powers. Trustees of unit trust do not have discretion as to the distribution of income. Discretion can be achieved by holding units in a discretionary trust.

A company lodges a tax return and pays company tax on its taxable income. The tax paid is held by the ATO, in the name of the company. When the directors decide to, the company pays dividends to its shareholders. The dividends, when paid, carry with them a “franking credit” being the tax previously paid by the company. The dividend is then called a “franked dividend”. This ability of the directors to decide when to pay dividends, and how much to pay, provides a significant tax-planning opportunity (more on the franking of company dividends later).

The general company tax rate is presently 30% of every dollar of taxable profit. Companies that meet the definition of a “small business enterprise” (“SBE”) pay company tax of 28.5% of their taxable income.

Australian resident individual taxpayers pay tax at different rates on progressively higher levels of income, ranging from 0% on income up to the tax-free threshold (presently $18,200) up to 45% on taxable income above $180,000.

Medicare and other levies also apply, bringing the maximum possible personal rate to 49.5%. Small, unincorporated businesses receive a discount on the personal income of tax paid on their business income.

The difference between the corporate rate and individual rates creates opportunities for tax planning. There is a point at which less tax is paid by earning profits in a company as against having it taxed in the hands of individual taxpayers.

From a taxation perspective, it becomes worthwhile considering incorporation when an individual’s taxable income from a business begins to approach $80,000. Income left in a company is taxed at 28.5% or 30% instead of (up to) 49.5% including Medicare in the hands of the individual.

Incorporation provides other significant tax-planning opportunities. For instance, dividends might only be paid in years in which shareholders had low incomes. Or, the company shares might be owned by discretionary trusts, so the trustees of those trusts have discretion as to where the income lands within their family group.

When the shareholders are approaching retirement, it can be advantageous to accumulate franking credits by not paying dividends. After the directors retire from business and their incomes are low, they can commence paying dividends and receiving franking credits. Those franking credits, received in years of low income, can result in tax refunds for several years.

The Capital Gains Tax consequences of transferring your business to a company or a trust need to be considered. Also, there are Capital Gains Tax (CGT) consequences when the business is eventually sold. There are CGT concessions available to Small Business Enterprises and they need to be considered.

After incorporating, it is usual for the proprietors to become employees of the incorporated entity. Salaries are paid to them with tax deducted at source and PAYG Summaries are issued at the end of the year. Their employer is required to pay superannuation and provide usual employee benefits.

Costs of Incorporation

The decision to incorporate a company or company and trust structure is often made after long and detailed discussion. Once the decision is made to go ahead, the process as we do it at DBA Accountants is highly systematised to control costs. The two parts of the process are invoiced separately – the discussion and advice leading up to the decision takes as long as it needs to take and is charged on a time basis, then DBA Accountants carries out the implementation of the incorporation at a fixed price.

The fixed price service is paid in advance and covers all of the following:

- instructing solicitors, receiving and checking the ir documents,

- lodgments as required with regulators,

- transfer or registering business names,

- minutes of initial meetings of directors and/or trustees,

- applications for Tax File Number, Australian Business Number and GST registration,

- PAYGW registration as necessary,

- explaining and signing of documents, and

- providing checklists of actions you need to take and guidance on how to do it.

The cost of incorporating an entity is claimed as a tax deduction by the entity. If the entity is registered for GST, it claims back the GST included in the incorporation cost in the first BAS lodged.

Costs of Transferring a Business

There may be costs involved in transferring a business from one type of ownership structure to another. For instance:

- Duty on the value of assets transferred, including Goodwill

- Valuations of the business and individual assets within it

- Capital Gains Tax on the sale of the business – and the possible application of CGT concessions

- Transfer of employees and revision of employment contracts

- Review of estate planning strategies and documents

We discuss these and deal with them as necessary for your situation – and your circumstances are different to anyone else’s, so there is no “one size fits all” solution.

Ongoing Costs, Once Incorporated

An incorporated entity or a trust will, in almost all cases, require more paperwork and record-keeping than an unincorporated business such as a sole proprietor or a partnership. This will involve more work for you and for DBA Accountants. For instance:

- More and more complex financial reporting to members and more reporting to regulatory bodies (eg ATO and ASIC) means that accounting fees will be greater than previously.

- Annual fee to the Australian Securities & Investment Commission (“ASIC”).

- Workers Compensation insurance for directors (you), if you wish.

- Compulsory superannuation contributions for directors.

People have different opinions about the value of workers compensation insurance and superannuation. Some people think of workers compensation insurance for themselves as an unnecessary expense – we think of it as an important protection. Some people think the eventual sale of their business will provide all the retirement money they need – we think a superannuation fund is an essential long term savings mechanism and estate planning strategy.

Franking of Company Dividends

Quote from the ATO website:

“Dividends paid to shareholders by Australian resident companies are taxed under a system known as ‘imputation’. It is called an imputation system because the tax paid by a company may be imputed or attributed to the shareholders. The tax paid by the company is allocated to shareholders by way of franking credits attached to the dividends they receive.”

Company tax paid is recorded in a company’s tax return, in a schedule called the “franking account”. The franking account is like a statement of the company’s tax bank account with the ATO. Company tax payments can be looked at as interest-free loans to the ATO, to be withdrawn at the director’s discretion.

How it works is easier to explain with working examples.

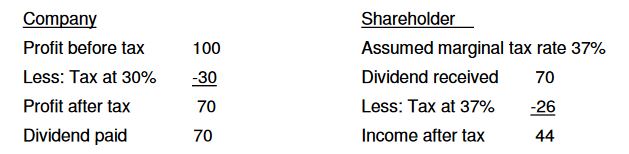

Before the imputation system was introduced, this is what happened:

A company would earn a profit and pay tax on it at the company rate of tax. The company would pay a dividend to its shareholders. The shareholders would pay tax on the dividend at their personal rate of tax. The result was that company dividends were taxed twice.

Like this:

The result was double taxation, being $30 + $26 = $56, or 56% of the original $100 company profit, even ignoring levies, such as Medicare. And our example individual taxpayer is not on the highest personal rate of tax.

The imputation system was introduced in 1987. With company tax now eventually flowing to the dividend-receiver, double taxation ceased. But not entirely…

Profitable companies that pay company tax and retain their after-tax profit to reinvest in their business can then go broke and never pay a dividend. In those cases, the ATO keeps the company tax that would otherwise have become a franking credit attached to a dividend.

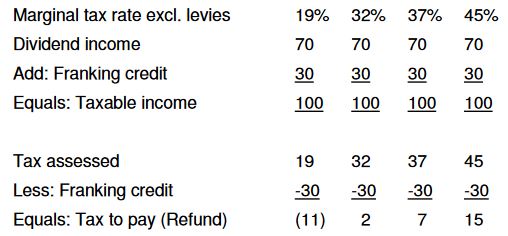

These are the income tax outcomes for a franked dividend:

Our example company earns $100, pays $30 company tax and pays a fully franked dividend of $70 to its shareholder. At different marginal tax rates, this is the effect in the tax return of the individual shareholder.

If the franking credits exceed the tax assessed, the taxpayer receives a refund of the excess from the ATO.

Under the imputation system, the maximum rate of tax paid on a company profit is never greater than the maximum rate of tax paid by an individual resident taxpayer on the same income.

Directors’ Responsibilities and Liabilities

If you have become a director of a company, you need to be aware of your personal responsibilities and liabilities.

The Corporations Act places these responsibilities on directors and officers of companies:

- The duty to exercise your powers and duties with the care and diligence that a reasonable person would have which includes taking steps to ensure the company keeps adequate records, that you are properly informed about the financial position of the company and ensuring the company doesn’t trade if it is insolvent.

- The duty to exercise your powers and duties in good faith in the best interests of the company and for a proper purpose.

- The duty not to improperly use your position to gain an advantage for yourself or someone else, or to cause detriment to the company.

- The duty not to improperly use information obtained through your position to gain an advantage for yourself or someone else, or to cause detriment to the company.

A director has personal liability for the following:

- Debts incurred while their company traded insolvent

- Lodgment of documents with ASIC

- Unpaid PAYGW and compulsory superannuation.

Estate Planning Issues

Estate Planning is the organised, life-long process of accumulating financial assets, protecting them, and disposing of them appropriately on your death.

When you establish a business and create trusts and companies, they need to be considered in your estate plan. You add layers of complexity to your estate and they must be dealt with.

For guidance, we suggest you read “First you live…” Then talk to us.

Looking Ahead

A Business Plan is a powerful tool for a business, providing it is brief, relevant and flexible. It is the process that is most valuable – forcing you to examine your assumptions about everything to do with the business and become very realistic about what you intend doing.

Not many businesses prepare a Business Plan and many of those that do, produce a document intended to impress their bank and which they then ignore. In our view, a waste of time and money.

You could add value to your business as a (potentially) saleable asset and set it on stronger legal foundations by conducting an Add-Value Due Diligence with our help.

General Business and Financial Advice

An underlying philosophy behind what we do at DBA Accountants is that we help our clients ask the right questions. We believe that if our clients ask the right questions of us, then we have an opportunity to provide better value, with better targeted advice and service and as a direct result, we will help our clients increase their wealth.

We suggest you read the following books by DBA Accountants former director, Murray Davey and all available through the website.

- First you live…

- DBA Accountants Guide to Having Money

- DBA Accountants Guide to Business: First Principles

Special Reports published by DBA Accountants and relevant to all businesses are available here on our website:

- When You Change Your Business Structure

- Thinking About Self-Managed Super

- Closing a Business

- Employer Obligations